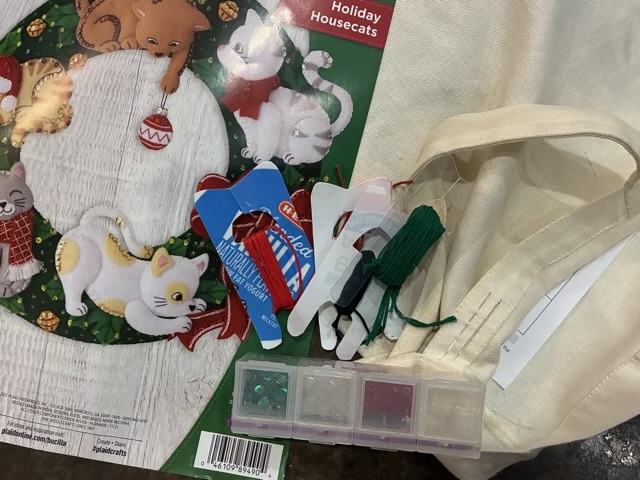

I bought a felt sewing kit two years ago, and just found it again while I was looking for something else. Since I have a dozen works in progress, what is one more? I really did try to put in back in the storage space, but it called to me. The first step was reading through the instructions (yes, I’m one of those), then prepping the materials and finding a project bag. I used bobbins cut from waste plastic to sort and hold the embroidery thread, and a small pill holder for the sequins and beads. The instructions suggest a plate, but I know myself and at the first distracted moment I would bump the plate and send seed beads all over the room. So I keep them on lock down. Yes, it takes a little longer to open the case, get out a bauble, then close the case, but it is better than picking them up off the floor and separating out the cat hair.

Now to see how long it holds my attention and how long it takes to finish.