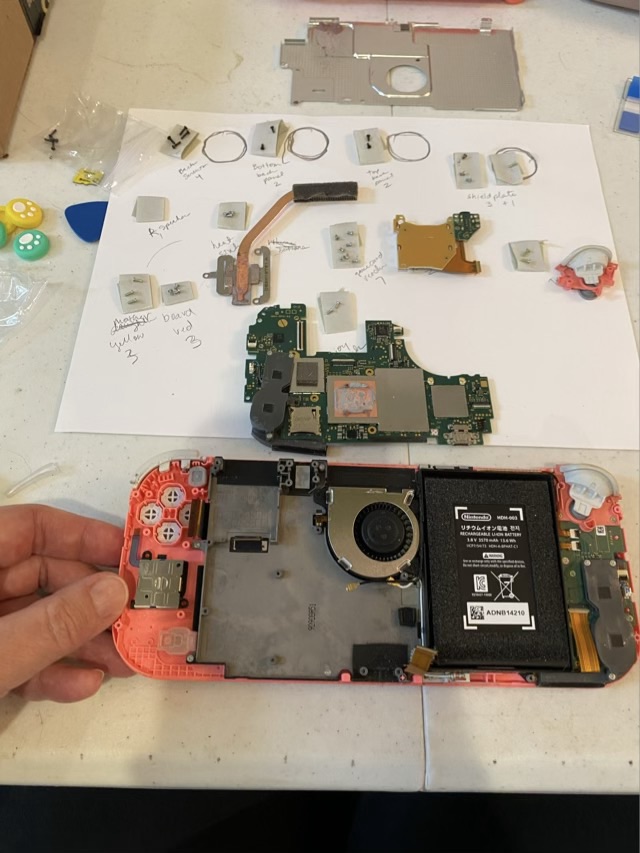

My youngest’s Nintendo Switch lite broke. The left joystick actually flopped around, not just drifted. She received a new to her full size Switch for her birthday, so the old one was a wash. Since it didn’t hurt anything to try, I bought an under $20 joystick repair kit and found directions. The directions had 28 steps just to get the joystick out, then the same 28 steps were retraced to put it back together. The kit came with two joysticks, which looked identical, except for part numbers on the back. There was no indication anywhere which was left, and which was right. I picked one. The disassembly didn’t go too bad for the left joystick, although I did break the left speaker connection because I didn’t realize that the plug was a teeny tiny white part in a slightly larger tiny white socket.

Feeling brave, and while the device was open anyway, I decided to replace the right joystick as well, after all, I had the part. Oh dear. The right joystick is a whole different set of steps, and involves removing a motherboard. I didn’t break the right speaker, and I had to replace the motherboard three times before all the cables were in the right spots, I thought. I missed the fan cable, and when I tried to retrieve it through the motherboard, it tore. Nuts.

Things I learned in this process: don’t force it (honestly I really should have known this, this is not my first rodeo). The engineering and durability of these devices is amazing. If I hadn’t been ham-handed, this is a doable repair. Inverted washi tape rings make great holders for tiny screws. Label everything. I saw my eldest set up for a deconstruction this way with wells embossed into card stock and it is brilliant.

The number one thing I was forcefully reminded of in this project: stop when you’re ahead.

The pieces and parts are now marked for a trip to tech recycling.